Many Australians would be unaware of how much Indians have contributed to this country. Indians have traded with Australia since the first European settlement; they have lived and worked here for over two hundred years. Yet we don’t often hear about this aspect of Australian history. The exhibition, ‘East of India: Forgotten trade with Australia’ currently being held at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney is a welcome opportunity to learn more about this.

Many Australians would be unaware of how much Indians have contributed to this country. Indians have traded with Australia since the first European settlement; they have lived and worked here for over two hundred years. Yet we don’t often hear about this aspect of Australian history. The exhibition, ‘East of India: Forgotten trade with Australia’ currently being held at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney is a welcome opportunity to learn more about this.

Understanding historical context is vital in good histories and this exhibition provides plenty of that. The items shown in ‘East of India’ weave a story of power, wealth, violence, culture and everyday life. The visitor is first immersed in the history of colonial India starting from the time when the Portuguese adventurer, Vasco da Gama, became the first European to find a sea route to India, to the Indian Rebellion in 1857. During the age of empire it was the sea, not the land which provided the transportation through which European nations dominated the globe.

‘East of India’ has some stunning exhibits, among which is a map on a parchment from 1599 with a section of the northern coast of Australia labelled as ‘beach’. I couldn’t help thinking how appropriate that label is! I was also attracted to a tiny locket commemorating the wedding in 1662 between Charles II of England and Catherine of Braganza, Portugal. What struck me as remarkable about the locket was not its form, but the enormity of what it represented. Catherine’s dowry included the Portuguese territory of Bombay (now Mumbai). I found it staggering that the wedding between two people could have such great repercussions for people who lived in a place that required months of arduous travel to reach.

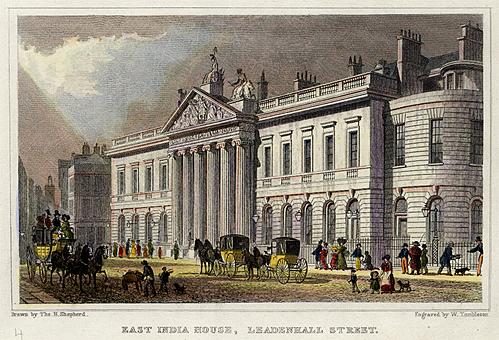

The other drawing which I gravitated to was of the East India Docks in London by William Daniell. On the drawing he wrote that the area of water covered by these docks was thirty and a half acres and the area reserved for the Company’s inward bound shipping catered for eighty-four ships. The sheer scale of the operations of the East India Company is staggering.

Yet the East India Company was reviled by many of the British themselves as the cartoons in the exhibition demonstrated. None of the wealth and power that the East India Company once held could protect them from the consequences of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The palace that was East India House was not just sold, it was demolished. Lloyds of London now stands where the seat of the once invincible company used to dominate the street.

Palakollu, Andhra Pradesh, Coromandel Coast, India, c. 1740 – 1780

Collection: Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Photo: Andrew Frolows. Reproduced with permission from the Australian National Maritime Museum.

India was renowned for its cloth in Europe. In the exhibition visitors can see some stunning designs but I also appreciated the simpler things such as the explanation of what chintz is. Chintz was the English name given to the cloths painted in vibrant colours with dye that Indians called kalamkari.

Care has been taken for the exhibition to appeal to a variety of senses. Delicate fabrics must remain behind a glass screen but a cloth is designed for the touch a well as its visual appeal. Visitors are encouraged to feel a number of samples of khadi – the traditional Indian hand-woven cloth.

Sound is incorporated into the exhibition at a few points. Visitors can hear a song, ‘Jessie’s Dream: A Story of the Relief of Lucknow’ composed by John Blockley and lyricist, Grace Campbell in the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion. There is also a reading of one stanza of a poem, ‘Jhansi Ki Rani’ (The Queen of Jhansi) in Hindi and English eulogising an Indian heroine of the Rebellion.

I was thoroughly absorbed in the exhibition when I entered the sections focussing on Indian-Australian connections. The English had a well-established presence in India by the time that the first fleet landed in New South Wales. Crucially, India was significantly closer to Australia than Britain so permission to trade with India was granted with the third fleet. In 1791 Governor Phillip sent a ship to Bengal to gather supplies for the struggling colony in the antipodes; thus commenced an important trading relationship between the two colonies. Perhaps it is the everyday nature of the trade between India and Australia historically that has caused it to be overlooked. Between 1791 and 1845 seven hundred and sixty ships left Sydney to India and twenty-four ships capsized on these routes between 1797 and 1849.

It was not only goods that were exchanged between the two colonies. People also came. Many of the English who worked in India retired to Australia instead of returning back to England, Tasmania being a favoured destination. Indians worked in Australia but at times there was controversy over their terms of employment. In a sound booth visitors can hear actors reading the testimony given by Indian servants to New South Wales magistrates in 1819 complaining about their poor treatment at the hands of a Mr. Browne. This method of presenting the testimonies to visitors works well (more background on this exhibit here). Visitors can also see a contract of indenture signed by one of the Indians working as a servant in Australia. The exhibition notes bring the visitor’s attention to the controversy over such terms of indenture. Such contracts were considered too close to slavery by the British in Australia.

I was reminded of Fiona Paisley’s book, The Lone Protestor. Paisley briefly touches on the early history of people from the subcontinent and their relationship with Aborigines in nineteenth century Sydney and Western Australia. A ship’s roll is shown with the names of seaman thought to be Lascars (the name given to seamen from India) and visitors can see a Sydney Gazette issue describing an Islamic procession by Bengali seamen in Sydney in 1806. However, the exhibition notes share the observation that there are few records surviving about the Lascars of Sydney.

I was further reminded of The Lone Protestor when looking at the items about the Prinsep family who lived in India for many generations. Charles Prinsep founded the Belvedere Estate in Western Australia from where he sold horses to the Indian army. He also exported jarrah sleepers for use by the Indian railways. In The Lone Protestor Paisley mentions Charles Prinsep’s son, Henry, who was the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia and the recipient of letters of protest written by the Aboriginal man, Fernando.

Horses were also exported to India from New South Wales. Among these exporters were the East India Company itself. It purchased a property near present day Blacktown in 1845 and used it to breed horses for the Company’s army in India.

From the middle of the nineteenth century the exhibition fast-tracked to the twenty-first century. At the end of the exhibition visitors can sit down to watch a film specially commissioned by the Australian National Maritime Museum, ‘Indian Aussies – Terms and Conditions Apply’ This is an enjoyable and gently thought-provoking way to end the exhibition (read more about this film here)

I had finished viewing the exhibition, yet there were things I had expected which were missing. Where was the reference to the camels and the Indians who managed them who were so crucial to life and the economy in inland Australia during the latter half of the nineteenth century? I also had expected more focus on Western Australia as I knew that the relationship with India was particularly strong in this colony.

I guessed at the answer – space. This exhibition is large already. How could the curators have included the rest of the history? I asked the assistant curator of the exhibition, Michelle Linder, and she confirmed my suspicion. The curators had decided that the exhibition needed to be limited to the Indian and Australian history up to the mid-nineteenth century. However, this is not mentioned in any of the literature I have read about the exhibition produced by the Museum hence my expectations. For this reason I found the end of the exhibition rather abrupt.

I was thoroughly engrossed in the exhibition. When I emerged I was shocked when I looked at the time. In total I had spent nearly four hours in the exhibition and missed eating lunch. So there were some missing histories. No exhibition can cover it all. Clearly this exhibition had the depth to captivate me to the extent I lost all track of time.

This exhibition brings together a fascinating collection of items from a large number of Australian and British institutions. New South Wales institutions such as the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Dixson Galleries of the State Library of New South Wales and the Powerhouse Museum contributed items. There were items from the British Museum, the British Library, the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston contributed some items as did the National Trust of Australia.

If you have a chance I recommend that you make the effort to see this exhibition. There are many items I have not mentioned in this review which I am sure will captivate others. This is a unique opportunity to see these items in one place and to immerse yourself in a different depiction of our history.

Disclosure: I received a free ticket to view this exhibition from the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Additional Information

Additional Information

‘East of India: Forgotten Trade with Australia’ is showing until 18th August 2013. Ticket information and access to some good background about the exhibition can be found on the Australian National Maritime Museum website. Museum staff have written a number of interesting blog posts about the exhibition on the Museum’s blog. There are some interesting events associated with the exhibition which you can check out here.

You can read my review of Fiona Paisley’s book, The Lone Protestor on this blog. It is good to note that this book has been recently shortlisted for the 2013 Ernest Scott History prize.

5/7/2013: Fellow history blogger, Chloe Okoli, has also reviewed this exhibition. You can read her review here. Each person views an exhibition in a different way, so Chloe’s review is quite different to mine. Take the time to check it out!

Fascinating and so much I didn’t know. Certainly a transnational exhibit. Thanks.

We are an intertangled world and have been for centuries. Are there any Indian connections with Texas?

Yes, a few came to my part of the state in the early 20th century mostly as merchants and peddlars. Many more professionals came to Houston, Dallas and other cities east of here more recently. I did a book on Asians Texans, published by the Institute of Texan cultures, that attempted to survey what we know about them historically. Actually it turned into a statement of how little good primary research has been done on the various Asian groups in the state and how many exciting stories are waiting to be told.

Your review of the exhibition really fit into what I have been reading in transnational histories. I appreciate it.

You are full of surprises Marilyn! What is the name of your book and publication details?

The Asian Texans, Marilyn Dell Brady. Institute of Texan Cultures, 2004. It’s not a scholarly book but part of a series about different ethnic groups who have come to Texas directed at students and the general public. I relied entirely on secondary sources. I envisioned an audience wanting to understand their own family histories. The editors had some requirements that I won’t have chosen, but I guess that is always true. I know much more about the groups and their customs now than I did when I wrote it. But the research was fun.

Great review. If I were in Sydney I’d go to the exhibition

Thanks Andrew. I am very conscious that most Australians live outside Sydney and won’t have a chance to visit this exhibition. While there is no real substitute for visiting this exhibition I hoped with this review I could at least share some of the history I learned through this exhibition.

I’d love to see this … and I know plenty of Indian families who’d love to see it too. (There’s a big Indian community in the area where I teach). I wonder if they will do a travelling exhibition of it at some stage.

Thanks for the great review Yvonne and I think your comments about the end of the exhibition are spot on, perhaps we could have included a timeline/panel giving an overview of links between Australia and India from the 1850s until the present day. I guess we learn something new with each exhibition. Hi Lisa, Unfortunately there are no plans to travel the exhibition as it consists fo numerous loans from overseas and we only travel some of our exhibitions. If you want to read a little bit more about the show my co-curator Nigel and I have written a few articles about the exhibition in our latest magazine Signals available in our store http://www.anmm.gov.au/thestore

Thanks Michelle

Museum curators have a very difficult job distilling complex history from a collection of objects and labels which have incredibly small word limits! However, limitations encourage creativity and innovation in relating history to the public. I could be bold enough to say that there is no such thing as a ‘perfect’ exhibition but the aspiration to create one generates great initiatives.

Hi Yvonne,

Greetings from an Indian student of British decolonisation currently residing in England!

Thanks for this lovely review of a fascinating exhibition.

As a student of ‘transnational’ approaches to history, this is of particular interest to me. Politically and economically, the India-Australia relationship has always remained under-explored. This exhibition directs one’s attention beyond superficial references to cricket and the English language that have dotted the political relationship. And from a historical disciplinary perspective, this is a welcome addition. As far as my (admittedly limited) knowledge goes, academic attention so far seems to have been focused mostly on the decolonisation era and the acrimonious Nehru-Menzies relationship.

One quick comment on the review: it’s ‘Hindi’, not ‘Hindu’. Just to make sure there is no confusion.

Thanks again and best wishes,

Usha

Thankyou Usha for your thoughtful comment. While I love cricket, like you I’m over the fact that we don’t discuss the full depth of the Australian-Indian relationship. In fact the video at the end of the exhibition has a dig at this obsession with cricket which drowns out other important aspects of the relationship between the two countries. It does this in a humorous way but no-one could miss the point.

Thankyou for pointing out my error too! I’ve fixed it now 🙂

Thanks for this review, Yvonne. Really gave me a sense of the exhibition as a whole. I’m aware that Asian Australian work as I know it is heavily biased towards East Asian heritage groups, so initiatives that provide insight into South Asian histories and groups are very welcome.

I agree, both East Asian and South Asians have made significant contributions to Australian history. Where I can I try to write about Indian connections in Australian history on this blog because that history has a lower profile here.

Hello Perkinsy Wish I lived closer to see this for real !

I have just stated a Family history for my Partner with connection to India and the Princep Family. Our great grandfather Hookum TChan work for the Princep Family, and they saved his life by spiriting him out to W.A. Hookum was a Furniture Maker ,and has a Music Stand in The Canberra Art Museum and a sideboard here in the west made for the Princep Family. We are having a ball learning all about our Indian ancestry !!

That sounds very interesting Julie. It sounds like you may be able to dig up some history which would be interesting to many people outside your family. I wish you all the best for your research.