Participants at the recent Global Digital Humanities conference will remember the prominent contributions of Australian historians, Tim Sherratt, Julia Torpey and Peter Read. But I also want to highlight the more low profile but no less important contribution of Australian cultural institutions in bringing Australian historical records to world attention.

Participants at the recent Global Digital Humanities conference will remember the prominent contributions of Australian historians, Tim Sherratt, Julia Torpey and Peter Read. But I also want to highlight the more low profile but no less important contribution of Australian cultural institutions in bringing Australian historical records to world attention.

Australian governments and other funding bodies have shown international leadership by funding significant digitisation programs that have are freely accessible to the people of the world. This contribution to the world’s bank of knowledge is inestimable. As I listened to the papers presented at the Global Digital Humanities Conference I was struck by just how significant digitised Australian historical sources are for researchers around the world.

The Trove website is the flagship of Australia’s digitisation programs. Led by the National Library of Australia, with significant contributions from Australia’s state libraries, it is truly a treasure trove of all sorts of digitised items, including its famed digitised newspapers as well as the catalogue records of hundreds of cultural institutions around Australia. It is a massive online resource.

We would expect Australian researchers to embrace this resource, as they do, but researchers from other countries are also using Trove’s resources in cutting edge work. Every day we researchers presented papers which referred to Trove. Every day one of these papers was presented by researchers who worked for universities or cultural institutions outside Australia.

These papers, like all papers at the conference, demonstrate world class research in the field of digital humanities. As the conference proceeded it became clear that Trove has made an important contribution to leading international research.

There is something we should ponder.

At the end of the paper I delivered to the Australian Historical Association Conference in the week following the Global Digital Humanities conference I drew attention to the difficult funding situation faced by all Australian cultural institutions. Staff are asked to increase their productivity while their colleagues are retrenched because of budget cuts. This is affecting their services to the public. I arrived at the National Library of Australia on the weekend recently to find that no deliveries of items are made on weekends for orders received after 3:45pm on Friday. The weekend is often the only chance that someone can visit Canberra to do research. Often researchers only realise that they need a particular item after consulting another item they have pre-ordered. A research trip can be ruined by this curtailment of the Library’s services. This restriction to access is particularly onerous for the majority of Australians who live outside Canberra and can only travel to the capital on the weekend for research.

The National Library of Australia simply does not have the funds to provide staff to go to the stacks and retrieve the items on weekends.

Digitisation helps to increase access but the vast majority of historical items are not digitised and will not be digitised for decades. Access to the physical item will remain vital to research for years to come. Opening hours are a gateway by which information is made more or less open. With less funding comes more restricted access.

…governments are pumping out ‘open data’, bringing the promise of greater transparency, and new fuel for the engines of innovation. But for all its benefits, open data isn’t. It only exists because decisions have been made about what is valuable to record and to keep – structures have been defined, categories have been closed.

Tim Sherratt, ‘Unremembering the Forgotten‘, 2015.

Archives and libraries are not like our bedroom cupboards. We cannot just chuck government documents into our archives and quickly shut the door so it looks tidy. Documents need to be properly catalogued so they can be found. What ‘properly catalogued’ means to one generation is different to another, so old catalogues and documents need to be reviewed by succeeding generations to see if there is valuable information hidden in the archives (for example the ‘Indigenous Languages‘ project at the State Library of NSW). Knowledgeable staff need to be available to help researchers find what they are after. The physical condition of the archives needs constant maintenance and monitoring so mould and other nasties are kept at bay. Then there is the need to digitise records to increase access to them and to preserve them from handling. Digitisation represents another layer of intense, skilled work from archivists. Now government records are ‘born digital’ in largely paperless offices. These records require significant investment in information technology to store and skilled staff to supervise the initial archival process and ongoing care of the electronic records.

Archives require a lot of difficult and time consuming work to maintain and nurture them. A catalogue represents highly skilled work and I cannot see how the process of assessing a historic document and cataloguing it can be made quicker by productivity gains. It takes time and it takes care.

Archives need to prove to their funding authorities that their collections are used and highly valued. One way to do this is to count the hits on their catalogues, the number of downloads of digitised materials, the numbers of visitors to reading rooms, the number of requests for access to physical items.

But bland statistics can mask the quality of work. Funding authorities want to see high quality, innovative work being done with the digitised items. They need to see that people still value physical collections as well as the digitised documents. They need to see the value of the work of archivists and librarians and that this work should be fully funded.

Historians and digital humanists need to be vocal in their support of the work of libraries and archives. We need to help them demonstrate their value in their quest for better funding. One way to do this is to highlight the collections we use and to tell libraries and archives when we use them in papers and projects.

I have made a list of the papers which referred to Trove below. Abstracts are still available on the conference website. The website provides keyword searching which only revealed one paper that used Trove. I knew there were others so I made this list by viewing all abstracts for each day and doing a ctl + F search for the word ‘Trove’. I didn’t want to exaggerate the significance of the mentions of Trove in the abstracts so I have distinguished between papers with minor references to Trove and the majority of papers on the list which used Trove resources or referred to the Trove platform in a more substantive manner.

I have made a list of the papers which referred to Trove below. Abstracts are still available on the conference website. The website provides keyword searching which only revealed one paper that used Trove. I knew there were others so I made this list by viewing all abstracts for each day and doing a ctl + F search for the word ‘Trove’. I didn’t want to exaggerate the significance of the mentions of Trove in the abstracts so I have distinguished between papers with minor references to Trove and the majority of papers on the list which used Trove resources or referred to the Trove platform in a more substantive manner.

The conference abstracts are much more detailed than what we normally expect from a conference abstract so are worth while reading. The collections of other Australian cultural institutions were also mentioned during the Conference but I have not had a chance to identify those papers.

I would like to see the abstracts for papers delivered at digital humanities conferences and history conferences include a brief ‘Collections Used’ section. This section would list the cultural institutions and their collections which have been used for the paper. It would only need to be a few words, but including a ‘Collections Used’ section in the abstract would highlight the value of the work of archives and libraries and make it easier for Cultural Institutions to track the quality use of their collections. Would it be too much to ask conference organisers to then quickly create a Statement of Collections Used by all the papers presented? This could be added to the conference website and thus make it easier still for cultural institutions from around the world to identify the use of their collections.

Highlighting the collections used by researchers could be a simple, but effective way for researchers to acknowledge the debt they owe cultural institutions and the highly skilled work of the archivists and librarians in managing the collections.

Global Digital Humanities Conference 2015 – Papers which referred to Trove

- ‘Discovering and Rediscovering Full Text: Unearthing and Refactoring’, Kerrey Kilner, University of Qld (Australia); Kent Fitch, University of Queensland (Australia).

- ‘Enriching the HuNI virtual Laboratory with Content from the Trove Digitized Newspapers Corpus’, Toby Nicolas Burrows, University of Western Australia (Australia), Kings College London (UK); Alwyn Davidson, Deakin University (Australia); Steve Cassidy, Macquarie University (Australia).

- ‘Remapping Cultural History? Digital Humanities, Historical Bibliometrics, and the Reception of Print Culture’, Mark R. M. Towsey, University of Liverpool (UK), Katherine Bode, Australian National University (Australia), Simon Burrows, University of Western Sydney (Australia), Julieanne Lamond, Australian National University (Australia), Mark Reid, Australian National University (Australia), Glenn Roe, Australian National University (Australia), Sydney Shepp, Victoria University of Wellington (NZ)

- ‘Making Digital Aural History’, Alistair Thomson, Monash University (Australia); Kevin Bradley, National Library of Australia (Australia).

- ‘The Harpur Critical Archive’, Paul R Eggert, Loyola University Chicago (US), University of New South Wales Canberra (Australia); Desmond Allan Schmidt, Loyola University Chicago (US), University of New South Wales Canberra (Australia).

- ‘Bringing to life the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages’, Cathy Bow, Charles Darwin University (Australia).

- ‘Why Standards are Critical: Graphing Knowledge by Building on Well-Established Entity-Relationship Standards Can Look Well into the Future’, Ailie Smith, University of Melbourne (Australia); Marco La Rosa, University of Melbourne (Australia). This is paper 2 of the session – scroll down to find it.

- ‘Crowdsourcing the Text: contemporary Approaches to Participatory Resource Creation’, Daniel James Power, Kings College London (UK), University of Victoria (Canada); Victoria van Hyning, University of Oxford (UK); Heather Wolfe, Folger Shakespeare Library (US); Justi Tonra, National University of Ireland, Galway (Ireland); Neil Fraistat, University of Maryland (US).

Poster

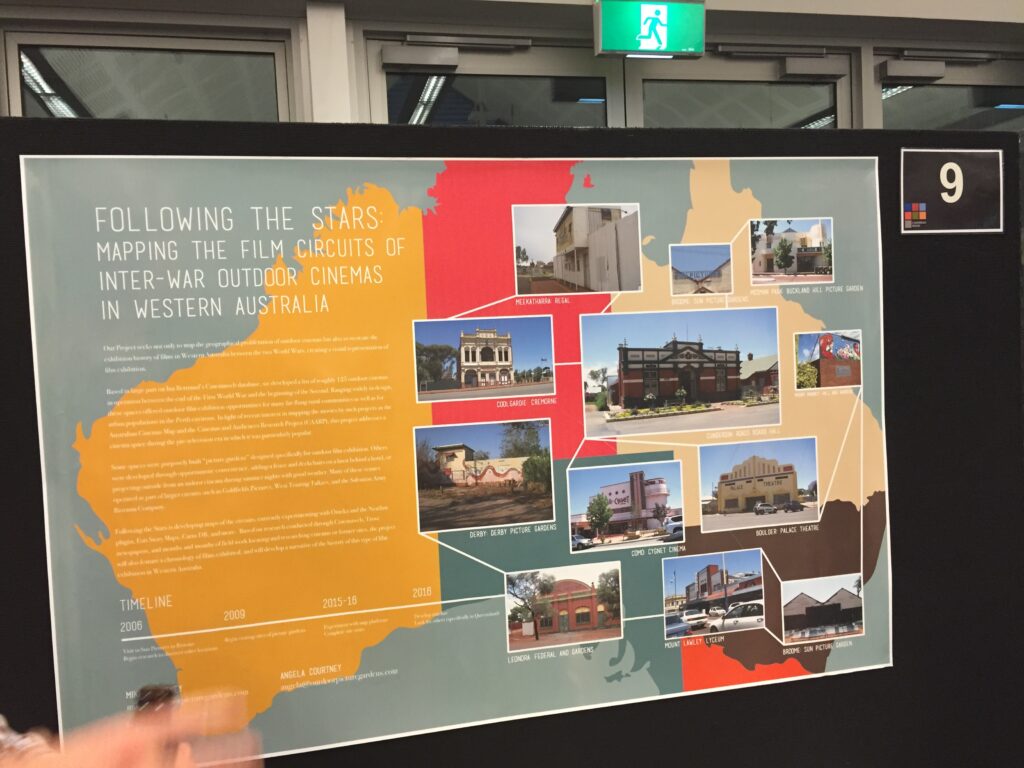

- ‘Following the Stars (Under the Stars): Mapping the Film Circuits of Inter-War Outdoor Picture Gardens in Western Australia’, Angela Courtney, Indiana University (US); Michael Courtney, Indiana University (US).

Minor Mention of Trove

- ‘Linked Open Data and the First World War’, Robert Warren, Dalhousie University (Canada); Mia Ridge, Open University (UK); Kathryn Rose, Memorial University (Canada); Valentine Charles, Europeana Foundation (The Netherlands).

- ‘Succession: Generative Techniques, Speculative Interpretation and Digital Heritage’, Mitchell Whitelaw, University of Canberra (Australia).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Further Reading

The following articles reference this post:

- Nickoal Eichmann, Jeana Jorgensen, Scott B. Weingart, ‘Representation at Digital Humanities Conferences (2000 – 2015)‘, the scottbot irregular, 22nd March 2016.

[…] International researchers value work of Australian libraries and archives. […]